Behind every ambitious project lies a personal journey. The Finance Reconsidered Chair, held at KEDGE Business School and supported by the Candriam Institute of Sustainable Development, owes much to Christophe Revelli — a former finance practitioner who left banking to pursue academic research in sustainable finance. This interview offers a closer look at the academic behind the Chair and at the convictions that continue to shape his work in sustainable and impact finance.

- Christophe, can you tell us more on your personal journey, and on what led you to sustainable finance?

After twelve years working across various industries, including a long stint in banking, I decided to leave my position just before the 2008 financial crisis to pursue a PhD in responsible and sustainable finance. This decision was closely linked to my experience in the financial industry, where I found that sustainability issues were not taken seriously, despite mounting societal challenges and growing funding needs.

I completed my PhD in 2011 and joined Kedge Business School in 2012, focusing on my research topics while developing new courses and specialised training programmes. In 2016, I founded the MSc in Sustainable and Impact Finance—the first Master’s programme in France and Europe fully dedicated to integrating sustainability into financial decision-making. I have also been the KEDGE-Candriam Chairholder for more than six years. - How would you describe the major phases in the development of sustainable investing research over the past twenty years?

For a long time, sustainable finance research remained marginal, confined to a nice academic literature. This began to change in the 2010s, with SRI becoming more mainstream and the signature of the Paris Agreement in 2015. This is when the scientific community started expanding the scope of research into sustainable finance.

Initially, research focused on the mechanisms that enabled ESG considerations to enter mainstream finance. Over the past decade, the emphasis has shifted toward financial materiality of ESG criteria—in other words, assessing whether ESG criteria represent a source of risk or profitability. Much of the literature has been driven by the question “Does it pay to be green?”. More recently, new asset valuation models and risk pricing models are emerging to incorporate ESG variables and adjust for ESG risks in a financial materiality approach: “sustainable-CAPM”, “ESG cash flows”, “carbon pricing”, the concept of a “greenium”… This had led to a proliferation of theoretical and empirical research proposing ways to integrate ESG variables into financial models. - The regulatory agenda is heavy, how have the new frameworks (SFDR, CSRD, ISSB, etc.) reshaped your research agenda? Are current sustainability disclosures sufficient to support reliable quantitative research?

Research naturally follows market developments. Regulatory evolution has brought academic attention toward reporting and disclosure frameworks such as ESRS and IFRS-S standards. The concepts of double materiality and impact materiality are now gaining traction in the literature, particularly as consensus grows around the decoupling between ESG financial materiality and actual positive impact on ecosystems.

Sustainable investing does not inherently deliver higher or lower returns; rather, performance depends on asset management quality, commitment, investment horizon, and asset class selection. However, sustainable investing does not systematically generate positive impact.

Historical data remain insufficient to meaningfully study the effects of double materiality—and regulatory simplification initiatives are unlikely to accelerate progress in this area. However, a new wave of researchers is beginning to analyse the financial mechanisms that hinder impact generation, notably through contributions from the social studies of finance. - Which academic or industry research breakthroughs do you see as having most profoundly changed investor behaviour?

I believe that research on ESG financial materiality has profoundly transformed the practices of stakeholders looking for quantitative models to identify the most profitable and highest-rated companies and sectors from an ESG perspective. However, academic work has also highlighted the limitations of these approaches, notably due to the poor quality and inconsistency of ESG data.As a result, many practitioners have adjusted their R&D approach, moving away from an exclusive reliance on external ESG data providers and toward more internalised approaches to mitigate rating biases. At the same time, a whole field of research is beginning to show that intentionality and additionality are critical for impact control — linking financing to clearly identified green projects rather than simply investing in companies with high ESG ratings.

- What research gaps must be prioritized in the coming decade if finance is to contribute effectively to climate and social transitions?

While research must remain neutral and methodologically rigorous, it inevitably reflects ontological and epistemological positions linked to researchers’ intrinsic values.

In my view, sustainable finance must move beyond a narrow focus on financial materiality and seek to understand impact materiality—its mechanisms, determinants, and measurement tools. This requires integrating insights from the social sciences to better understand actors’ behaviours and their consequences, allowing us to look beyond purely financial horizons.

For initiatives to become performative, they must define their language, discourse, tools, and identity. This is precisely where we currently stand with regard to impact finance. - What message would you give to young researchers entering the field today?

“Do not seek to publish at all costs!”. The “publish or perish” system can sometimes detract from the meaning of research and from the researcher’s own values. Scientific progress requires clarity of identity, strong methodological rigour, and a commitment to validation and intellectual anchoring rather than individual visibility.

That said, sustainability and ecological transformation will inevitably shape research agendas in the coming decades. The field is vast and topics are numerous, young researchers would be well advised to engage with early and meaningfully. - Have your students’ profiles and motivations evolved over time?

Students today are far more aware of climate, environmental and social issues, which have been part of their education and daily lives from an early age. This awareness has translated into new forms of engagement, including student-led initiatives, and in some cases, protests against institutional partnerships deemed ethically questionable.

However, there remains a gap between students’ values and their academic or career choices, often driven by fear or conformism. Sustainability still suffers from the misconception that it offers limited career prospects, a narrative reinforced by public discourse and media coverage. In reality, some of the most promising career opportunities are in sustainable finance, where professionals with dual financial and extra-financial expertise remain scarce. It is up to us to continue making the case for these paths. - What skill sets should be considered “core” for the next generation of sustainable finance professionals?

Soft skills are just as important as technical expertise. While strong financial and quantitative skills are essential, it is equally important to understand the purpose and limitations of the financial tools. The question of meaning must be central to learning.

Future professionals must also master sustainability issues alongside political, communication and international dynamics—including emerging markets, North-South dynamics, energy geopolitics. Sustainable finance education must therefore be transdisciplinary, drawing on social sciences, biophysics, geophysics, energy, mathematics, philosophy and anthropology.

Ultimately, finance should remain a set of tools serving societal and ecological challenges, rather than a discipline disconnected from the world it is meant to support.

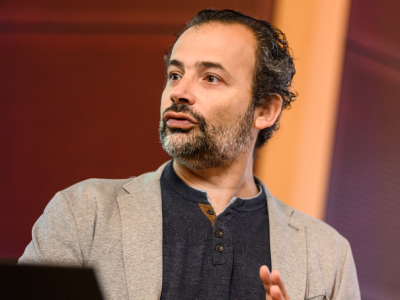

Christophe Revelli

At the crossroads of academic research and real-world finance, the Finance Reconsidered Chair reflects a long-term intellectual journey rather than a predefined model. Christophe Revelli’s path reminds us that rethinking finance is not only a technical challenge, but also a matter of conviction, rigor, and transmission.